Differences in state school and independent school pupil attainment were evident pre-COVID-19. However, recent GCSE and A-level results show that the pandemic has only widened these disparities.

The cancellation of official GCSE and A-level exams in England, due to social distancing measures, brought algorithm-determined grades in 2020 and teacher assessed grades in 2021. Both alternative grading measures encountered multiple issues, as well as outcries from the public due to large numbers of unfair grades.

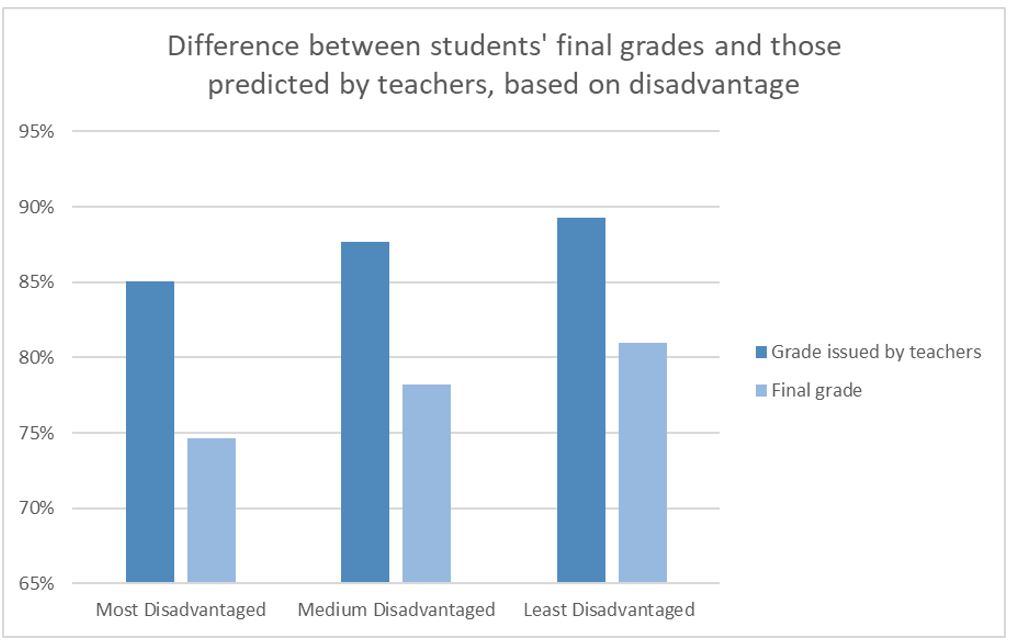

In 2020, teachers in England had approximately 40% of their A-level assessments downgraded by the algorithm introduced by exam regulator Ofqual. It was clear that the algorithm disproportionately impacted the most socioeconomically disadvantaged students:

Percentage of candidates achieving grade C and above in 2020.

Source: Ofqual and The Guardian.

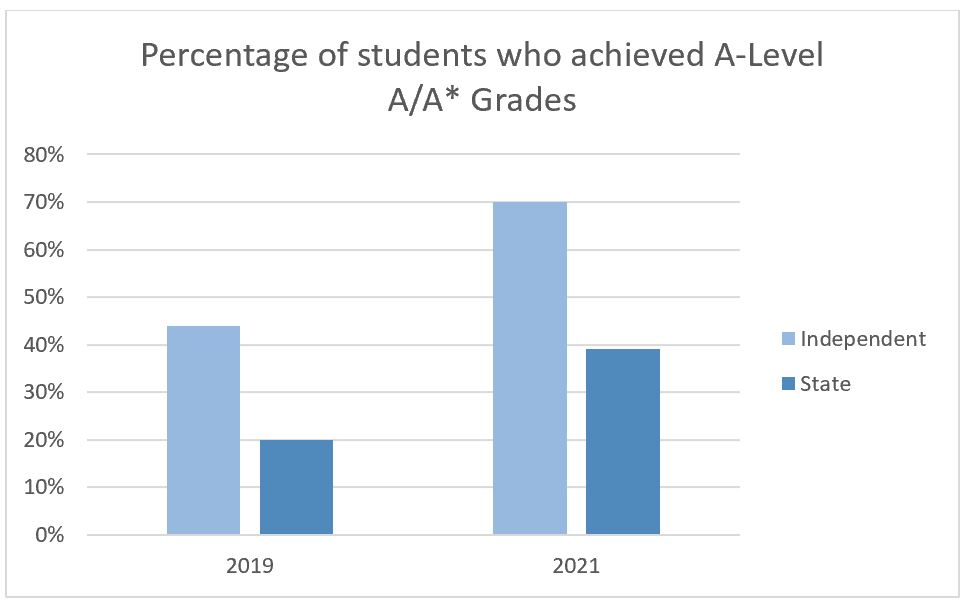

2021 only brought further polarisation between independent and state school pupils. Teacher assessed grades replaced formal exams in 2021, as Ofqual scrapped the use of their failed algorithm from 2020. However, the data for GCSE and A-level results in 2021 again suggests that the system was biased towards students in private education, in comparison to state school students.

The percentage of pupils achieving A-level A and A* grades has increased overall since the last year when formal exams were taken (2019). Yet the data highlights that the increase in pupils who achieved the highest grades was around 7% higher for independent schools, with 70% of pupils achieving A/A* grades in 2021—compared to 39% of state school pupils.

Source: Ofqual and PoliticsHome

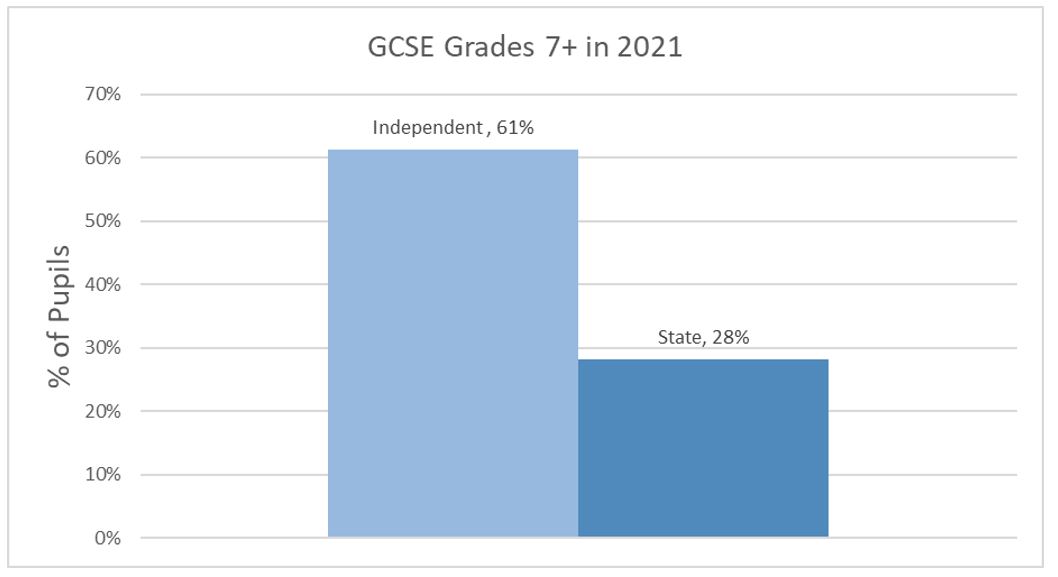

The picture is exceptionally similar with the top GCSE results (grades 7+) in 2021, where independent school pupils achieved significantly higher grades than their state school counterparts:

Source: Ofqual and PoliticsHome

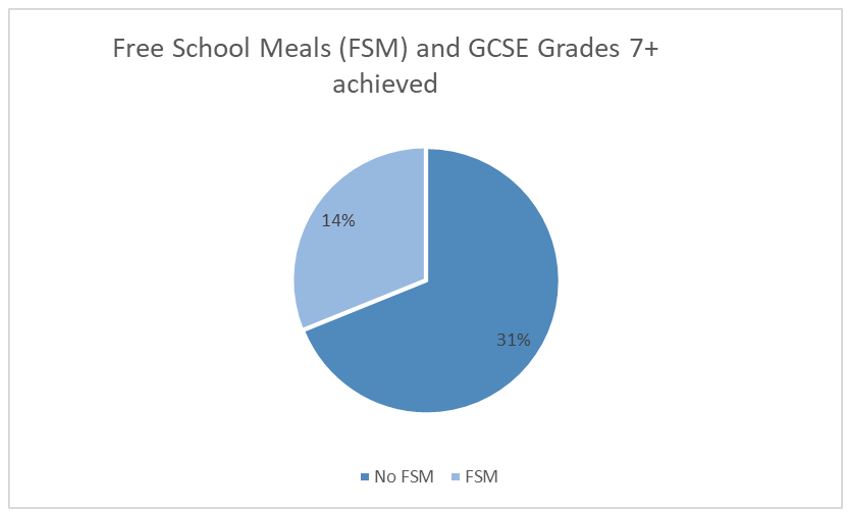

In terms of pupil attainment in state schools, a lower percentage of students on Free School Meals (FSM) achieved the top GCSE grades in comparison to those not receiving FSM, again highlighting the underlying socio-economic inequalities in UK education.

Source: PoliticsHome

We know that COVID-19 is not the only factor in play here, and that differences persisted prior to the pandemic. However, this widening gap can possibly be attributed to the significant disruption and lost learning time throughout the past two years.

In an interview with the Guardian, David Robinson of the Education Policy Institute said that even when “controlling for prior attainment” students “from disadvantaged backgrounds were worse off by at least a tenth of a grade compared to those from more affluent backgrounds”.

Furthermore, an academic review investigating the effects of COVID-19 on increasing inequalities in London found that educational penalties, as a result of school closures, may have been much more severe for families in worse off socioeconomic positions. This can be attributed to a lack of financial means for online tuition and digital educational resources, to replace education that is usually provided in person.

Future possibilities and solutions

As a new school year begins, and social distancing restrictions have all but been eased, the question remains of how to address increasing inequalities within UK education, especially within a post-pandemic era. More needs to be done to help those students who have been most disadvantaged due to the pandemic, to ensure that the past two years do not affect their future possibilities in post-18 education, or their career opportunities.

One solution comes from Cambridge University, which recently announced that they have created a ‘STEM SMART’ scheme to aid disadvantaged students who are entering post-16 education. Cambridge University academics will offer tuition to state school pupils who have had their education disrupted due to COVID-19. However, the scheme focuses on STEM subjects exclusively.

Conversely, Tony McAleavy, Research Director at Education Development Trust, suggests mapping access to technology and understanding the digital needs of pupils to deliver successful online learning and catch-up lessons. This also includes finding out what online access pupils have and what devices they have access to, as online learning is likely to continue in the coming months if pupils have to self-isolate, or if restrictions are re-introduced. Digital poverty has been a large issue throughout the pandemic, so funding must also be increased for schools in harder-hit areas to enable access to technology for catch-up learning.

In terms of funding, school and college leaders recently wrote to Education Secretary Gavin Williamson to ask for a temporary “catch-up premium” (worth £1,250 a head) for pupils on free school meals and a post-16 premium for those struggling with Maths and English.

Free tuition, technological access, and funding increases are all potential solutions to begin to close the inequality gap in UK education; but perhaps smaller charities and organisations, such as ours, could be offering support to pupils in the form of mentoring and general guidance, with the aim of reassuring students about their results—and aiding them in reaching their future career goals.